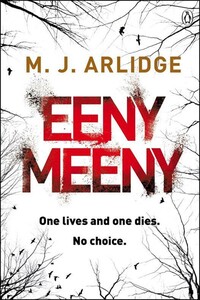

Luke scrambled through the open window and on to the narrow ledge outside. Grasping the plastic guttering above his head, he pulled himself upright. The guttering creaked ominously, threatening to give way at any moment, but Luke couldn’t risk letting go. He was dizzy, breathless and very, very scared.

A blast of icy wind roared over him, flapping his thin cotton pyjamas like a manic kite. He was already losing the feeling in his feet – the chill from the rough stone creeping up his body – and the sixteen-year-old knew he would have to act quickly, if he was to save his life.

Slowly he inched his way forward, peering over the lip of the ledge. The cars, the people below seemed so small – the hard, unforgiving road so far away. He’d always had a thing about heights and, looking down from this top-floor vantage point, his first instinct was to recoil. To turn back into the house. But he stood firm. He couldn’t believe what he was contemplating, but he didn’t have a choice, so releasing his grip, he hung his toes over the edge and prepared to jump. He counted down in his head. Three, two, one…

Suddenly he lost his nerve, dragging himself back from the brink. His spine connected sharply with the iron window frame and for a moment he rested there, clamping his eyes shut to block out the panic now assailing him. If he jumped, he would die. Surely there had to be another way? Something else he could do? Luke turned back towards the window and looked once more at the horror within.

His attic bedroom was ablaze. It had all happened so quickly that he still couldn’t process the sequence of events. He’d gone to bed as usual, but had been wakened shortly afterwards by a chorus of smoke alarms. He’d stumbled out of bed, groggy and confused, waving his arms back and forth in a vain attempt to disperse the thick smoke that filled the room. He’d managed to scramble to the door, but even before he got there, he saw that he was too late. The narrow staircase that led up to his bedroom was consumed by fire, huge flames dancing in through the open doorway.

The shivering teenager now watched as his whole life went up in smoke. His school books, his football kit, his artwork, his beloved Southampton FC posters – all eaten by the flames. With each passing second, the temperature rose still further, the hot smoke and gas gathering in an ominous cloud below the ceiling.

Luke slammed the window shut and for a second the temperature dropped again. But he knew his respite would be brief. When the temperature inside grew too great, the windows would blow out, taking him with them. There was no choice. He had to be bold, so turning again, he took a step forward and calling out his mother’s name, leapt off the ledge.

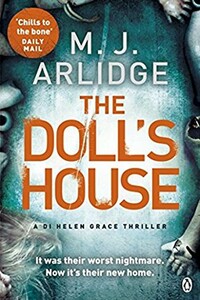

It was almost midnight and the cemetery was deserted, save for a lonely figure picking her way through the gravestones. Simple crosses sat cheek by jowl with ornate family tombs, many of which were decorated with statues and carvings. The weatherworn cherubs and angels of mercy looked lifeless and sinister in the moonlight and Helen Grace hurried past them, pulling her scarf tight around her. The scarf had been a Christmas present from her colleague Charlie Brooks and was a godsend on a night like this, when darkness clung to the hilltop cemetery and the temperature plunged ever lower.

The frost was slowly spreading and Helen’s feet crunched quietly on the grass as she left the main path, darting left towards the far corner of the cemetery. Before long she was standing in front of a plain headstone, which bore neither name nor dates, just a simple message: ‘Forever in my thoughts’. The rest of the headstone was blank – with no clue as to the deceased’s identity, age or even sex. This was how Helen liked it – it was how it had to be – as this was the last resting place of her sister, Marianne.

Many criminals go unclaimed on their death. Others are quickly cremated, their ashes scattered to the winds in an attempt to blot out the very fact of their existence. Others still are buried in faceless HMP cemeteries for the undesirable, but Helen was never going to allow that to happen to her sister. She felt responsible for Marianne’s death and was determined not to abandon her.

As she looked down at the simple grave, Helen felt a sharp stab of guilt. The anonymous nature of Marianne’s epitaph always got to her – she could feel her sister pointing her finger at her accusingly, chiding Helen for being ashamed of her own flesh and blood. This wasn’t true – despite everything Helen still loved Marianne – but such was the notoriety of her sister’s crimes that she’d had to be buried without ceremony, to avoid the prurient interest of journalists or the justifiable ire of her victims’ relatives. Safety lay in anonymity – there was no telling what some people might do if they found out where this multiple murderer had finally come to rest.

Helen was the only person present at her sister’s committal and would be her sole mourner. Marianne’s son was still missing and, as nobody else knew of the grave’s existence, it fell to Helen to battle the weeds and honour her memory as best she could. She came here once or twice a week – whenever her shift patterns and hectic work schedule allowed – but always in the dead of night, when there was no chance of being followed or surprised. This was a private, painful duty and Helen had no need of an audience.